|

من شعر الإمام الشافعي إذا المرء لا يرعاك إلا تكلفاً The poetry of Imam Shafei If one cares for you only begrudgingly Translated By: Nadia Selim To hear a performance of this: https://youtu.be/F2C7SaqVOG4 إِذا المَرءُ لا يَرعاكَ إِلّا تَكَلُّفاً فَدَعهُ وَلا تُكثِر عَلَيهِ التَأَسُّفا If one cares for you only begrudgingly, let them be, and do not waste your regret on them فَفِي النَّاسِ أبْدَالٌ وَفي التَّرْكِ رَاحة وفي القلبِ صبرٌ للحبيب ولو جفا There are others, and peace in departure, but in the heart there is patience for those whom we love even when they are harsh فَمَا كُلُّ مَنْ تَهْوَاهُ يَهْوَاكَ قلبهُ وَلا كلُّ مَنْ صَافَيْتَه لَكَ قَدْ صَفَا Not all whom you love will love you, nor will all whom you are sincerely pure with, reciprocate إذا لم يكن صفو الوداد طبيعةٍ فلا خيرَ في ودٍ يجيءُ تكلُّفا If sincerity is not in their nature, then there is no good in receiving warmth proffered begrudgingly ولا خيرَ في خلٍّ يخونُ خليلهُ ويلقاهُ من بعدِ المودَّةِ بالجفا There is no good in a friend who betrays his friend and meets their warmth with harshness وَيُنْكِرُ عَيْشاً قَدْ تَقَادَمَ عَهْدُهُ وَيُظْهِرُ سِرًّا كان بِالأَمْسِ قَدْ خَفَا And denies a friendship of old, and reveals secrets that were once hidden سَلامٌ عَلَى الدُّنْيَا إذا لَمْ يَكُنْ بِهَا صَدِيقٌ صَدُوقٌ صَادِقُ الوَعْدِ مُنْصِفَا Farewell to the world, if it does not offer a fair, sincere friend that keeps their promise

2 Comments

https://www.amust.com.au/2019/02/ibn-khaldun-arabic-and-the-quran/

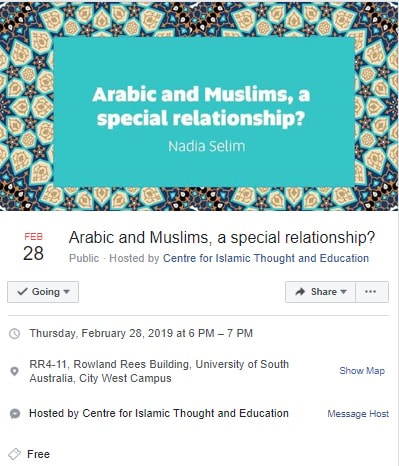

In recent years, Muslim teachers and learners of Arabic, have become focused almost solely on the Holy Qur’an as a source of language learning. However, in doing so, rather than become more faithful to Islamic educational thought we seem to have strayed from the positions of well-known scholars such as Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406). Ibn Khaldun explained in the Muqaddimah that the Arabic of the Qur’an, being divine and inimitable, cannot be emulated by learners or indeed anyone else. Therefore, the increased focus on it as a means of acquiring language ability is impractical. Ibn Khaldun, having conducted ethnographic research on Arabic teaching and learning in the Islamic empire went onto explain that the Moroccan peoples (Maghreb) focused on the Qur’an alone and as a result could not develop a good command of the Arabic language, whereas the Spanish (Andalusia) grasp of the language was far superior because of their inclusion of other readings. He qualified this with a statement that the religious knowledge of the Spaniards was not as advanced but was sufficiently supported by their knowledge of Arabic, which gifted those who wished to pursue their religious study with the tools they needed to do so. In fact, Ibn Khaldun highlights that the Judge Ibn al-‘Araby preferred the Spanish (Andalusian) position which prioritized Arabic and poetry as he lamented the fact that many children were reading texts without comprehension. To learn more about the ground-breaking thought of Ibn Khaldun in the space of language learning, you can read a recently published academic paper that compiles and encapsulates his arguments entitled: Arabic, Grammar and Teaching: An Islamic Historical Perspective. It has been traditionally understood that Muslims hold a special place in their hearts for Arabic. Why are Muslims encouraged to learn Arabic? Does Arabic shape the worldview of Muslims? This presentation seeks to illuminate some aspects of the historic Islamic scholarly perspective on Arabic as a language of culture and identity for Muslims. The presentation also raises questions about emergent trends in the Muslim community that have seen some Muslims forsake Arabic and their consequences. Come and join us on the 28th of Feb 2019 (In Sha Allah) at a free public lecture at the University of South Australia. The Facebook Event is shown below as is the Eventbrite Link.

Learning Arabic: Are we going to remain indifferent? (PUBLISHED IN THE AUSTRALIAN MUSLIM TIMES)11/10/2018 https://www.amust.com.au/2018/10/learning-arabic-are-we-going-to-remain-indifferent/

Muslims have always identified with Arabic as a language of religion. However, research suggests that Arabic teaching remains challenged by a lack of resources, poor teaching approaches and a diminishing supply of suitably trained teachers. Academicians have brought these issues to the attention of educators through various conferences and workshops without effecting any significant change, both within Australia and without. It is as if we are locked in a vicious cycle. For instance, as far back as 1984 a workshop held in the South African district of KwaZulu-Natal, emphasized that inadequate teaching methods had been in use in secondary school Arabic classrooms since their inception and that because of this students were abandoning their study of Arabic and that it was necessary to rebuild love for Arabic. In the following year, this workshop was followed by another attempt to orientate teachers at a local school. Moreover, the Association of Muslim Schools conducted numerous seminars successively. Unfortunately, in 2002 two South African researchers (Mall and Nieman) found that teaching methods had not changed to any significant degree and concluded that problems were not tackled genuinely and that action plans were not actualized. In the Australian context, in 1993, researchers issued a report on the status quo of Arabic in Australia, and their research suggested that resources, teacher training and student attrition needed attention. Moreover, they emphasized the need to develop programs for genuine second language learners, i.e. non-Arabs. However, as recently as 2013, Peter Jones reported that Australian Muslim students of non-Arab backgrounds were quite dissatisfied with their Arabic learning at Islamic schools. We are certainly aware of the issues anecdotally as well. Many non-Arab Muslims will speak of their failed attempts to acquire proficiency in the language or moan about their children’s dissatisfaction with their Arabic courses. So what is the problem? Why, do we choose to turn a blind eye? Why are Muslim educators not championing change? This can only mean one thing. As Muslims, we speak of the special relationship we have with Arabic but we do not translate this into work and effort. In my view, the persistence of these problems has its roots in indifference. An indifference to the purpose of Arabic in our lives as Muslims, an indifference to our role as educators, an indifference to striving for excellence, and indifference to each other as educators and most unfortunately an indifference to our responsibility of delivering the key of the Quran and Sunnah successfully to future generations. The pressing question is, as Muslims, are we going to remain indifferent? Ibn Sahnun: visionary educator of the 9th century (PUBLISHED IN THE AUSTRALIAN MUSLIM TIMES)18/6/2018 https://www.amust.com.au/2018/06/ibn-sahnun-visionary-educator-of-the-9th-century/

In an increasingly polarised world, it is important to highlight Muslim achievements in various areas of scientific endeavour and their role in the European Renaissance. In the field of education, the work of the scholar Muhammad ibn Sahnun (or Ibn Sahnun), who lived in the 9th century (817 – 870 CE), is a shining example of the progressive nature of Islamic thought in the field of education. In 2006, Professor Sebastian Günther* explained that “Insufficient awareness of the educational achievements of the past bears the risk of not recognizing what is genuine progress in the field of education and what is mere repetition.” Gunther further explains that Western researchers on education often neglect “theories, philosophies, and intellectual movements originating from cultures and civilizations other than the occidental one”. This makes highlighting such thought a matter of critical importance. Ibn Sahnun was born in Kairouan in Tunisia to a reputable and religious family. His father Sahnun was a jurist known for his piety, justice, and investment in the education of both his son and daughter. Ibn Sahnun was primarily educated in Kairouan under the keen eye of his father, who is known to have said; “Teach my son by praising him (appreciating) and speaking softly to him. He is not the type of person that should be trained under punishment or abuse. I hope that my son will be unique and rare among his companions and peers. I want him to emulate me in the seeking of knowledge.”* In his early thirties, Ibn Sahnun embarked on a pilgrimage and journey of learning in Egypt and Hejaz (Saudi Arabia). Ibn Sahnun became a productive scholar respected for his God-consciousness, generosity, and kindness. Above all, Ibn Sahnun became a visionary educator when he deliberated on education. He is credited with setting out the first framework for the development of an educational curriculum in a book called Kitab Adab al-Mu’alimin (The Book of Teachers’ Ethics) or “Rules of conduct for teachers”. One might think of this work as the first iteration of a “teacher’s manual” or “handbook” because it dealt with administrative, ethical and professional issues. In describing this work, Günther notes that it “provides us with an idea of the beginnings of educational theory and curriculum development in Islam while at the same time showing that certain problems relating to the ninth century continue to concern us today.” Günther further notes that this 1000 year old work deals with “aspects of the curriculum and examinations to practical legal advice in such matters as the appointment and payment of the teacher, the organization of teaching and the teacher’s work with the pupils at school, the supervision of pupils at school and the teacher’s responsibilities when the pupils are on their way home, the just treatment of pupils (including, e.g., how to handle trouble between pupils), classroom and teaching equipment, and the pupils’ graduation.” This 12-page treatise continues to inspire research. Most recently, the work of Ibn Sahnun was deemed relevant to educators developing Arabic curricula for young Muslim non-native speakers. ————– * Sebastian Günther, 2006, ‘Be Masters in That You Teach and Continue to Learn: Medieval Muslim Thinkers on Educational Theory,’ Comparative Education Review 50, no. 3 *Translated by Sha’ban Muftah Ismail, 1995, ‘Muhammad Ibn Sahnun: An Educationalist and Faqih,’ Muslim Education Quarterly 12, no. 4 https://www.amust.com.au/2017/11/living-a-translated-islam-learn-arabic/

Umar Ibn-ul-Khattab (ra) was to become renowned for his unfailing justice and asceticism. The story of his acceptance of Islam is well known to Muslims. A powerful man both in physique and demeanor storms home enraged by the knowledge that his sister and brother-in-law have converted to Islam. Bellowing and thundering, he is stopped cold in his tracks by the power, beauty and excellence of the Qur’an. The verses had such power over him because he comprehended them. He was shaken to his core because he filtered what he perceived through a meshwork of a deep-seated knowledge of the Arabic language and appreciation for its subtleties and cadence. Centuries of love for the Arabic language, have been firmly rooted in the fact that Arabic was the language that Allah chose to communicate his final call to humanity. For instance, Ali Al-Farisi (901-987 CE) a famous grammarian and linguist, when asked to compare Arabic and Persian, replied that Arabic “was far superior to Persian both aesthetically and rationally”. This love for Arabic meant that Arabic was claimed by Muslims of all cultural backgrounds. Arabic became a binder of the ummah, a language of Muslims and not just a language of the Arabs. In fact, many of the renowned Arabic scholars and grammarians were of non-Arab origins. Today, however, it has become commonplace for Muslims to practice deen without having acquired knowledge of the Arabic language or having tried to acquire it. Various societal transformations have normalized this phenomenon and made it acceptable for millions of Muslims to live a translated Islam. What is sadder, however, is that some Muslims value other languages more. It is acceptable for Muslims of certain ethnic backgrounds to send their children to memorize the Qur’an verbatim in Arabic, and then learn all their deen in their local language. Initially used as aids, if at all, these local languages have been elevated among some groups to such a degree that they have supplanted Arabic as a language of deen. It is indeed true that with the multitudes of translations present today, the basic tenets of the faith, such as belief in the oneness of Allah, the truth of the Prophethood of Prophet Muhammad (s), Allah’s commandments and his prohibitions can be articulated in any language and enacted whether one knows Arabic or not. However, enactment of deen, articulation of religious statements, recitation of verses verbatim and connection with deen are very different things. The Qur’an in Arabic is profound, but millions are disconnected from the words of Allah and barred from experiencing the miracle of the Qur’an in Arabic. Lesley Hazelton, an agnostic Jew, took it upon herself to read the Qur’an in Arabic and English and concluded that in English the Qur’an was a mere shadow of itself. Indeed, anyone who knows any language knows that the beauty of its literature cannot be experienced in translation, especially when translations are mediated by translators influenced by their views, backgrounds, experiences and agendas. More importantly Arabic was a language of identity for Muslims. The Islamic civilization did not eradicate local cultural norms provided they did not contradict the teachings of Allah, i.e. Islam did not have a one-culture policy. However, there was never any disagreement among Muslims that Arabic was the language of the ummah. Ibn Taymiyyah (1263 – 1328 CE) considered the learning of Arabic fard because it facilitated comprehension of the Qur’an and the Sunnah. More importantly, Ibn Taymiyyah was many centuries ahead of contemporary scholars when he stated that acquiring a language had an influence on cognition, mannerisms and religiosity. He believed that learning Arabic constituted emulation of the righteous companions and that it would influence how Muslims viewed or perceived the world, thought about it and ultimately experienced Islam. He, therefore, illuminated the deep connections between language, culture, identity and worldview. The question here is, why are millions of Muslims satisfied with living a translated Islam? The bigger question is, are we fast approaching a time in which we will be carrying scrolls that we do not comprehend? Much research is needed to answer these questions and many others about the complexities of the relationship Muslims have with the Arabic language. In the Australian context, my PhD research seeks to understand the experiences of Muslim youth learning Arabic at Australian Islamic schools to shed light on their views of the Arabic language, detail the nature of their learning experiences and identify whether these experiences have an impact on the uptake of Arabic by Australian Muslim youth. Recently, I was asked an interesting question about how excerpts from the Qur’an can be used to teach students studying Arabic as a Foreign Language using Communicative Language Teaching methods. This blog entry aims to address this question. First, I will present some thoughts for consideration prior to inclusion of Qur’anic verses into Arabic programs. Secondly, I will offer suggestions for activities and tasks.

Inclusion of Qur’anic excerpts in Arabic programs; 1. Objectives for Arabic and Islamic subjects need to be different. Program developers should always keep their goals for the Arabic program distinct from their goals for Islamic subjects. More importantly, students, should be able to perceive that the goals of their Arabic subject are similar to the goals of their English language subjects and different to the goals of their Islamic subjects. Therefore, an Arabic program should not focus on memorization of verses and/or their recitation but should focus on the comprehension of the content of the verses when read and heard. Additionally, while Islamic subjects at schools introduce the Qur’an to young learners for recitation and memorization an Arabic program should not follow the same approach. 2. Careful selection of excerpts;

3. We should not teach to the excerpt but teach language and introduce an appropriate excerpt. In the same way that we should not be teaching to the test, we should not be teaching to the excerpt. Excerpts should be introduced after incremental learning of the target language items has occurred over a period of teaching and deemed acquired through coursework activities and/or assessment. Material could be slightly above the students' level but comprehension should not be contingent on teachers' translation. Possible classroom activities;

The connection between Arabic and Islam is clear, yet few Muslims have really learned Arabic and fewer Muslim children want to study Arabic as they get older. This reality is connected to the prevalence of beliefs about learning and teaching that are counterproductive at times.

One such belief is often expressed through statements such as; we don’t need to know how to communicate in Arabic or we just want to understand the Qur'an. Simply put, this belief defines Arabic as a tool of religious practice. Accordingly, this belief has led to Arabic often being equated with reading religious scripture and has caused teaching Arabic to become greatly based on translation and grammatical analysis of selections of religious text even when dealing with children. In practical terms this often involves hours of analyzing the grammatical functions of words as well as memorizing lists of verbs and vocabulary. This approach contradicts knowledge of and research into; what language learning involves and how it may be achieved. To better understand why this is problematic, please consider the following analogy. A refugee who has recently arrived in Australia and knows no English attempts to learn English by reading and grammatically analyzing Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Clearly, this refugee cannot achieve their goal by bypassing all stages of learning that would normally lead up to reading Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Similarly, if this refugee’s only goal was to read English with comprehension, starting with Shakespeare’s Macbeth and in this way would still be inappropriate. Firstly, due to the nature of the text and its difficulty. Secondly, because they would lack all of the prerequisite knowledge needed to understand or appreciate the work. While this is an ineffective course of action for an adult refugee, please imagine the futility of this course of action if the refugee was in fact a child. Although, many of us would agree Macbeth would be unsuitable for a five or even a ten-year-old, we give our children scriptural text when we try to teach them Arabic. Confining the learning of Arabic to; deciphering, translation and grammar study of scripture inadvertently causes more harm than good. This is especially true, when coupled with suggestions that we can bypass all stages of Arabic learning and dive into grammatical analysis, reading and translation of scripture, which is a linguistically complex example of the Arabic language. Additionally, while isolating a sub-skill of language, in this case reading, and equating it with all learning of that language is counter-intuitive, I find that choosing this approach when teaching children Arabic is an even more questionable decision. Yet, Children's Arabic classrooms are heavily invested in this choice of practice as literature on the teaching of Arabic indicates. Ultimately, these statements and associated learning and/or teaching behaviors point to a lack of understanding of two important facts. Firstly, that children and adults learn very differently. Secondly, that reading with comprehension is based on a communicative language ability. In this regard, one of the points of confusion is often the term "communicative". Many assume that this means "conversational Arabic" only and that pursuing this learning is in some sense frivolous. More importantly, they make this assumption and forget that even conversational Arabic requires a great degree of prerequisite knowledge. Communicative ability in a language typically includes “grammatical, discourse, strategic and socio-cultural” * knowledge that manifests aurally-orally and if the person is literate; in their reading and writing as well. Therefore, communicative competence in a language is:

However, more importantly these statements completely disregard the fact that the Islamic revelation was first and foremost an aural-oral revelation to and through the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ who is known to have been an “unlettered man”. If the Prophet had no knowledge of “reading and writing” it would be safe to say he was not a “grammarian” either (especially when we know that Sibawayh authored Al-Kitab, arguably the first written grammar codex, centuries after the Prophet’s passing). Naturally, the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was granted special knowledge and understanding of the message he was to convey, through his “communication” with Gabriel and because he was under the tutelage of the Almighty ﷻ. However, most of the people living in his time were not literate grammarians either, but still came to appreciate and glorify the “Quran” as “perfection” to a “miraculous” degree of; the linguistic, poetic, rhetorical and story-telling skills appreciated at the time of revelation. This appreciation, with which many of the public received the Qur'an, was built on comprehension that was firmly embedded in their “communicative competence” *. This communicative ability and competence was in effect; an inherent understanding of how Arabic worked grammatically, how this grammar manifested and should manifest in their daily discourse, a knowledge of word and phrase meanings and a socio-cultural understanding of appropriateness, idiomatic use, registers as well as a strategic ability to adapt verbal language and contextualize it so as to compensate for deficiencies in other areas should the need arise. This competence and associated prerequisite knowledge was gained through having undergone the natural developmental stages of attaining their; communicative Arabic. Even today, many illiterate Arabs in the Middle East , can tap into the surface level meanings of the words they hear in scripture through an understanding of communicative Arabic. They are consequently able to make connections with explanations of the text as well as appreciate the beauty of what they hear. However, unfortunately, many learners of Arabic as a Foreign Language (FL) and indeed many teachers of Arabic as a Foreign Language (FL) feel that they can bypass learning communicative Arabic and go straight to literary and grammatical translation of the text to attain an understanding of a heavily nuanced conversation between the Almighty ﷻ and his faithful that is embellished with literary jewels only knowledge of Arabic can reveal. This is unfortunately a myth that needs to be dispelled. * Savignon, S. J. (1987). Communicative language teaching. Theory into Practice, 26(4), 235-242. * Savignon, S. J. (2002). Interpreting Communicative Language Teaching: Contexts and Concerns in Teacher Education. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press. 0 Comments

The struggle with remembering vocabulary is the big elephant in any language classroom. One of the most important things to note in this regard is that: you are not alone. All students find mastering vocabulary a challenge. This is not a surprise given that the core vocabulary of any language is around 3000 words. Mastering vocabulary is essential so it is important to find ways that can help you remember the words better. Here are a few tips and tricks: 1. Songs / Music: wherever possible try to find a song that covers the target language and sing along to that although it sounds like a silly thing to do when you are a grown up. There is scientific evidence that suggests that even individuals suffering from dementia can recall words set to songs better. If there are no songs available it is really worth it to you to try making up your own. Set the words you aim to learn to a tune you know. That’s what advertisers on TV do… isn’t it? 2. Associations: we remember better when we connect what we are learning to things we already remember. There are many ways of doing this, so you have to find what works best for you and is best suited to what you are learning. You can associate new vocabulary with words you already know in the language you are learning, similar words in your native language or things you have seen, smelt, heard or experienced. Sometimes you may need to make silly associations. I find that this trick works best for me if I am tackling lists. Here are some examples: - Sulphur is yellowish in colour and sounds like the Arabic word aSfar / yellow. - Azure means blue and has an Az sound in it like the Arabic word azraQ / blue. - واحد / one : has one aleph in it (highlighted in red). - The letter ف (fa) looks like a fellow lying flat on his back. - Tuesday الثلاثاء sounds like the number three ثلاثة the middle chunk of Tuesday looks similar too. - قطة / cat sounds similar to the English word cat. - The letter ك looks like Aladdin’s shoe. 3. High traffic Lists: It is not a bad idea to make a short list of about 5 words using a big bright font and pin it up in the high traffics areas of your home like your fridge door for example. Look through the list very quickly when you go to get your next glass of water. Don’t stand and memorize the list, just look through it very quickly as you would a post-it note. 4. Repetition: here I am NOT referring to rote memorization. For example, when you repeat a telephone number over and over in your head to remember it. I mean repeat the learning in different ways. Try to see, read, listen, speak, write and play whenever you tackle any new vocabulary set. 5. Multi-task: Do your Arabic vocabulary alongside something else you do on auto-pilot. Here are some examples: - Using Arabic to workout. o If you are running on the treadmill put your list in front of you. Read your words as your run. o If you are doing sit-ups use your Arabic words to count. - If you are showering sing your Arabic song of the day. - If you are cooking listen to a recording you made/or have of the words. 6. Stay positive: the emotional roller-coaster associated with language learning is a reality. You have days when all is dandy and others when you’ve had enough. On the days when you are struggling to manage your chores, work, kids and vocabulary remember that it is not you and that language learning is a very hard thing to do. Make a conscious effort to approach the vocabulary set as a fun challenge rather than a horrible burden. However, do not force yourself too much. Maybe this is a day that you should dedicate to watching a film or listening to contemporary music in the target language. Language is the most important bridge to another person’s heart. One of my favourite quotes on this matter is by Nelson Mandela. Mandela explains that “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head” whereas “ If you talk to him in his language that goes to his heart.”

Learning language breaks down some cultural barriers, as language and culture are so intertwined that one could say that learning the language of a people is in fact a window into their culture. For when you learn another language, you gain some insight into the perspectives and spirit of the people who speak it. This will ultimately only add to you as a person and to your understanding of life. For as Federico Fellini says, “a different language is a different view of life”. These two points are essential because cultures are bound to meet through business, sharing of technology and knowledge, tourism and political endeavors. It is also a reality that when cultures meet; they are also bound to clash. This cultural interaction is necessary for as Ghandi says, “no culture can live, if it attempts to be exclusive”. This cannot ring any more true than in this age of globalized communication that has made interaction with the other effortless but has also increased chances of cultural misunderstanding and cultural misrepresentation. Essentially, whether you are traveling for business or leisure you will most probably meet people that are different to you and that speak another language and knowing the language of your destination can only enhance the experience for all other parties involved. As you will be able to appreciate the people, their arts and way of life a lot more. You will also have a better chance of making meaningful friendships and increasing business as well as work or overseas study opportunities. However, interestingly enough, learning another language hones your skills at your own language. For as you look at another language critically you are inevitably going to compare it to your own. What happens is you suddenly realize that you are learning things about your own language that you did not notice before because you have taken it for granted all along. In addition to becoming better acquainted with your own language and culture, as they are a packaged deal, you also keep your brain working and access areas that you may not have accessed earlier. In fact, research indicates that learning language helps with offsetting dementia by four or five years (refer to Thomas Bak and Suvarna Alladi’s work on bilingualism and dementia). Additionally, research in the areas of language acquisition shows that when you learn language you will also implicitly learn how to learn a language because your metalinguistic awareness increases. Ultimately, when you learn a language you add to your repertoire of cognitive and life skills a skill that cannot be isolated and taught at a school or university. Although research results in the area are mixed, there is evidence to suggest that competence in two languages increases chances of acquiring a third language. So what are you waiting for? 0 Comments

One of the first things to keep in mind is that less is more. So do not overwhelm yourself with long lists of vocabulary, many sheets of grammar or long hours of study. It is much better to work at learning a few words or concepts at any one time. Additionally, keep your study sessions short. I often tell my students that 5-10 minutes are enough if done regularly. Let us look at some practical examples: - If you are studying assigned words then choose the five most important ones and that will be your quota for the session. - If you are studying grammar (at any proficiency level) then focus on one concept only. So for example, if you are a beginner learning to use the attached pronoun my then that is your quota for the session. - If you are looking at verbs. Then first break up the task by either focusing on pure grammatical conjugations or meaning. a) If you are learning meanings, then take on only what you can chew and stick with the five-word quota. b) If you are studying conjugations then DO NOT attempt to learn all conjugations in one sitting. Focus on two at most. Do either the present and past tenses that correspond to a single pronoun or study two pronouns in a single tense. The second thing to keep in mind is that we all learn differently. Always bear in mind that what works for other people will not necessarily work for you and that this applies to both the technique and pace of learning. In terms of technique: think about how you learn other things best and then apply that technique to your quota. For example, rote memorization does not work for me. I find that I remember best if pin the words up where I can see them constantly without having to actively study them. In terms of pace: there is no speed limit associated with learning language. You can go as fast or as slow as you need to in order to succeed. You alone can be the judge of this aspect. Do not feel bad if you are slower than someone else is and do not get overly excited if you are better than someone else is. The question you should always ask yourself is: did I do everything I needed to, to get this far? If the answer is , yes, then the time you took to acquire what you did, is your pace. 29 Comments

Start blogging by creating a new post. You can edit or delete me by clicking under the comments. You can also customize your sidebar by dragging in elements from the top bar. 29 Comments Welcoming you all to the AWN Blog! 10/4/2012 04:51:42 amماذا قرأنا اليوم؟ |

Author: NADIAArchives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed